Safeguard and the Nixon-Kissinger Strategy

The BMD Debate III: Détente and Vietnam (1969-1974)

IN MOSCOW, May 1972, President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev signed two treaties completing the first phase of the U.S.-Soviet Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT).

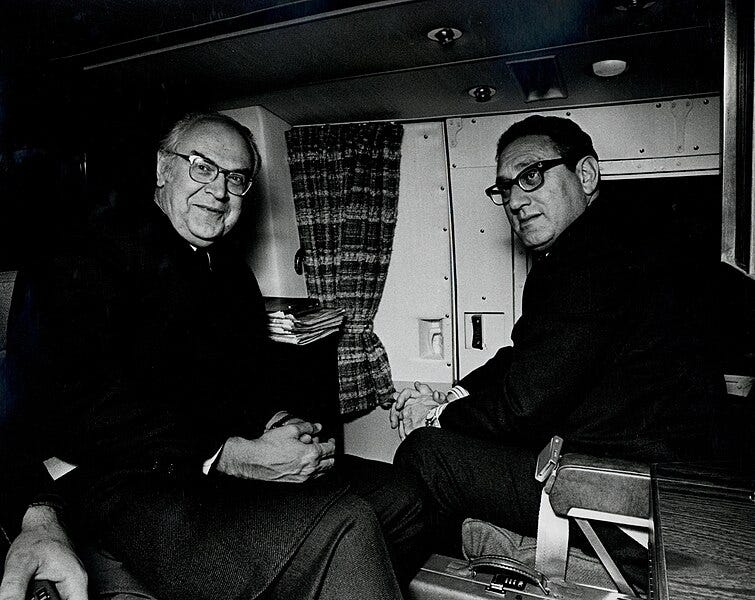

The Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty and the Interim Agreement on SALT (SALT I) established respective limits on the number of defensive and offensive weapons each superpower agreed to deploy. The treaties seemed to neatly square essential strategic problems in the ongoing ballistic missile defense (BMD) debate by formalizing a modus vivendi of mutually assured destruction (MAD). Each superpower agreed to accept mutual vulnerability to nuclear attack in return for providing the other with verifiable restraint from deploying national ballistic missile defenses. But despite their apparent symmetry, the 1972 agreements were the result of a complex, almost convoluted sequence of maneuvers by Nixon and his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, designed to maximize U.S. leverage in SALT. To procure this leverage, Nixon and Kissinger opted to introduce a new robust BMD system in March 1969, Safeguard, as part of the wider strategy to improve superpower relations and extricate America from Vietnam.

Safeguard’s role in the Nixon-Kissinger strategy was to provide the U.S. with a bargaining chip in the SALT negotiations, but the timing, nature, and development of the program was tied to a global strategy to improve superpower relations and extricate America from Vietnam. In the final years of the Johnson Administration, Lyndon Johnson had aimed to procure consensus on arms control with the Kremlin as a measure to help the U.S. withdraw from Vietnam. But BMD became the key obstacle in these negotiations after the Soviets refused to abandon Galosh, an anti-missile defense (ABM) system deployed around Moscow to shield it from a U.S. first strike. The basic controversy in the BMD debate was that missile defenses in one superpower homeland could obscure the other’s confidence in the destruction of their adversary, creating a situation that could escalate the arms race, as feared by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. Moreover, most BMD systems lacked technological credibility, but could still engender the illusion that a nuclear war could be survived, and in the process, threatened to make one more likely. Despite the Johnson Administration’s progress towards arms control, the superpowers’ dispute over BMD endured, and U.S. leverage began to decrease as the Vietnam War worsened. After entering office in 1969, Nixon was determined to strengthen U.S. leverage in arms control negotiations, resolve the BMD impasse, and only after improving superpower relations, end the Vietnam War.

To accomplish this daring agenda, however, Nixon and his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, approached ongoing arms control negotiations with the Kremlin in much the opposite way as Johnson had. Although both Administrations viewed improved relations with the Kremlin as essentially a prerequisite to withdrawing from Vietnam, Kissinger was adamant that to ensure U.S. leverage, Nixon had to in fact escalate tensions, including in Vietnam. Nixon’s experience with brinkmanship as Eisenhower’s Vice President led him to agree with Kissinger’s view that the only way to ensure Soviet cooperation over matters including BMD was to posture as a “Madman,” willing to take bold, unpredictable or even irrational action to achieve his objectives. The Nixon-Kissinger strategy was just as rooted in Kissinger’s questionable theory of “linkage,” which held that escalation in one theater (i.e., Vietnam) could be used to directly impact another (i.e, Moscow.) As such, though introducing Safeguard to the BMD race was fraught with its own escalation risks, the Nixon-Kissinger strategy was all-in, with Safeguard seen as essential in leveraging SALT, and the effects of SALT seen as necessary for “peace with honor” in Vietnam.

Nixon and Kissinger were notoriously secretive in their maneuvers, and within their strategy held many things in tandem, including Safeguard. By recurrently threatening to expand the system in the negotiations with the Soviet Union, they placed additional pressure on the Soviets to accede to U.S. positions on BMD. At the same time, they put additional strain on the Kremlin by normalizing relations with China. However, escalating the Vietnam War in attempts to influence SALT proved mostly futile, as the Viet Minh remained fiercely defiant despite the ensuing Soviet pressure upon them to negotiate with the Americans. Though Safeguard was successfully traded away for consensus on BMD in SALT through the ABM Treaty in 1972, and reduced by an additional protocol in 1974, the merits of the Nixon-Kissinger strategy remain dubious at best. Despite the new consensus in the arms race generated in SALT, improved relations with Moscow and Beijing failed to ensure a peaceful nor prompt exit from Vietnam. Moreover, the Safeguard maneuver and the other schemes hatched by Nixon and Kissinger may have fomented lasting distrust in superpower relations, despite the breakthroughs achieved in 1972.

1969 | SAFEGUARD

Nixon became president after superpower arms control negotiations had already been initiated, but remained deadlocked on the issue of BMD. In the last years of the previous administration, Lyndon B. Johnson had coined the acronym “SALT” to implore the Soviet leaders to focus on limiting strategic offensive nuclear weapons in the next phase of the negotiations. The Soviets had already moved ahead with U.S. diplomats on arms control agreements like the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and the day Nixon became President on January 20th, in a gesture of goodwill, the Kremlin announced its willingness to partake in SALT later in the year. Although the White House continued the negotiations on the NPT, Nixon and Kissinger desired additional leverage before starting SALT, particularly a stronger bargaining position on BMD.

On March 14th, Nixon announced Safeguard, and described it as a system designed to enhance deterrence by protecting U.S. Minuteman ICBM fields, thereby limiting the effectiveness of a Soviet first strike. He drew contrasts between this new system and Sentinel, announced in 1967, which had aimed to provide area defense at a significantly higher price. Although Nixon mused that Safeguard might grow to as many as 12 sites in the future, he only asked Congress to begin by approving two sites defending ICBM fields in North Dakota and Montana. However, the very same month, Kissinger clarified in a classified memorandum that “Safeguard could be used as a bargaining chip in SALT.” From here forward, Nixon and Kissinger played a double game in the superpower arms control negotiations and in Congress, feigning that Safeguard was a robust BMD system they fully intended to pursue, while secretly planning to discard it.

In the game with the Kremlin, the Soviet leadership reacted to the announcement of Safeguard with the wariness and concern Nixon and Kissinger had hoped. Soviet negotiators still working with the U.S. on the NPT began to sound like McNamara at Glassboro when they criticized BMD systems as inherently destabilizing. The Kremlin clarified its view on BMD after Nixon’s announcement, distinguishing between limited systems providing defense against “third-party” attacks like its own system, Galosh, and those like Safeguard designed to augment deterrence. It became increasingly evident to both U.S. and Soviet negotiators that to proceed with SALT, the superpowers would have to reach a new consensus on BMD.

In Congress, Nixon and Kissinger used the polarization of the BMD debate to obscure their intentions for Safeguard, and to create a policy best suited to trading it away for Soviet concessions at a later date. In June and July, Democratic critics argued that BMDs were inherently destabilizing and expensive, while Republican proponents emphasized their utility in protecting U.S. ICBM silos, defending against Chinese nuclear blackmail, and demonstrating U.S. resolve in the SALT negotiations. On August 6th, Vice President Spiro T. Agnew cast the tie-breaking vote in the Senate, approving funding for the first two Safeguard sites at Grand Forks, North Dakota, and Malmstrom, Montana. But before SALT was initiated that November, Nixon and Kissinger improvised to take advantage of external developments while implementing other preconceived schemes specifically designed to weaken Soviet leverage.

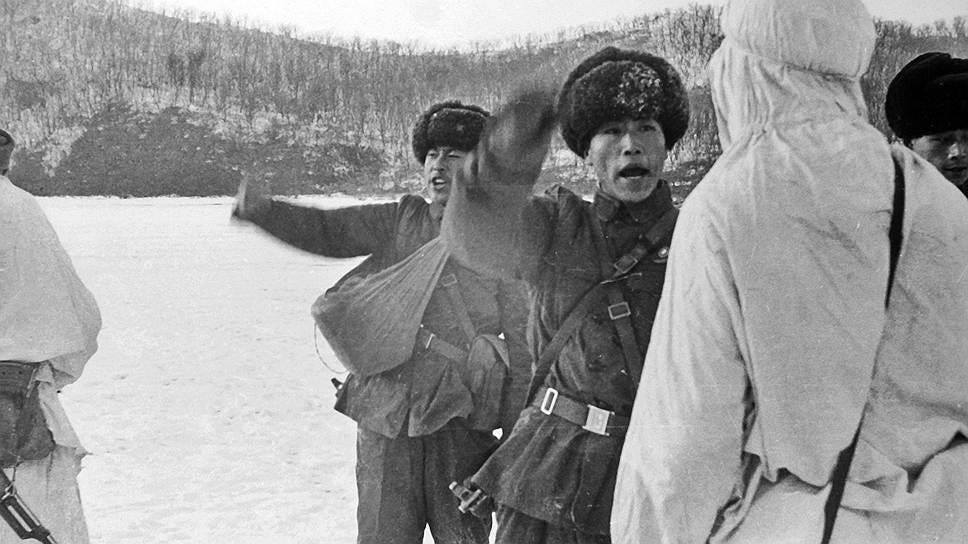

In the spring and summer of 1969, military clashes along the Sino-Soviet border had escalated into a low-intensity war between Soviet and Chinese forces. U.S. officials grew anxious that nuclear war might soon break out between the two powers. Although the Nixon Administration successfully employed “triangular diplomacy” to contain and de-escalate the conflict, Nixon and Kissinger noted the critical opportunity to “lean toward the Chinese against the Russians” to the U.S. strategic advantage. Despite their enduring concerns over Safeguard, the Kremlin’s interest in engaging the U.S. in effective arms control increased after the skirmishes. They now faced two adversaries on multiple fronts and the real prospect of an alliance between them. But Nixon, determined to exacerbate Soviet strategic inferiority and “link” SALT to Vietnam, implemented a preconceived tactic designed to enhance U.S. strategic leverage even further.

Between October 13th and 30th, Nixon implemented his so-called “Madman Theory” by placing U.S. strategic forces on a secret nuclear alert designed to ring alarms in the Kremlin. At the same time, he ramped up aerial bombing campaigns against the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and Cambodia that had begun earlier in the year. Nixon also ordered the U.S. Navy to conduct mining exercises in the Philippines to feign to Hanoi that the U.S. was considering mining Haiphong Harbor. All of these maneuvers were meant to signal to the Kremlin and the Viet Minh alike that Nixon was personally willing to take extreme, even irrational measures to achieve his ends, including the use of nuclear weapons. The Viet Minh, which the Nixon Administration still falsely judged as a puppet regime, proved unwilling to heed the Kremlin’s recurrent calls for restraint and goodwill in the Paris Peace Talks, however. But in the Kremlin, Nixon’s “calculated unpredictability” that October engendered the desired effect of raising the apparent price for Soviet intransigence in SALT.

As the SALT negotiations opened on November 17th, Nixon and Kissinger were confident they held the upper hand, believing they had begun to maneuver the Soviet leadership into a corner. Gerard C. Smith, Director of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, led the Washington delegation against Soviet negotiator Vladimir Semonov as the talks began in Helsinki, Finland. Contrary to Johnson’s original vision of SALT as a means to limit offensive nuclear arsenals with the added benefit of fostering consensus on BMD, the initial talks became dominated by BMD, largely due to the deliberate controversy stirred by Safeguard. At Nixon’s behest, Smith insisted on linking agreements on both offensive and defensive weapons, ultimately persuading Semonov to concede. Despite this apparent success, deadlock quickly emerged over defining “strategic” offensive forces and BMD itself. Nevertheless, Nixon had successfully steered SALT towards his preferred terms, setting the stage for a broader strategy over the next two years that aimed to exacerbate Soviet vulnerabilities in various ways in the wider Cold War.

1970 | DEADLOCK

With the construction of the first two Safeguard sites in North Dakota and Montana underway, in January 1970 Nixon requested a review of the options for expanding the system to provide area defense for metropolitan areas, specifically for the U.S. leadership in Washington D.C.. In his report, NSC Staffer Walter Slocombe weighed the pros and cons of what was later referred to as the “National Command Authority” (NCA) option. Slocombe noted substantial benefits the NCA option could provide in SALT, as it was the direct equivalent of what the Soviets intended for Galosh. He also listed the obvious military benefits, such as providing protection against small or accidental attacks and giving U.S. decision-makers additional time to issue attack orders and relocate in the event of a nuclear war. The disadvantages were also apparent; Congress might not approve funding, it would be widely expensive, and the technical credibility remained dubious. Slocombe’s overall conclusion was positive, however, suggesting that in any case the move would demonstrate U.S. resolve in BMD at a critical impasse in the arms race.

Although Nixon elected not to pursue expanding Safeguard to defend Washington D.C. until 1971, Slocombe’s report likely influenced the positions the U.S. delegation put forward in April 1970 when the negotiations resumed in Vienna. At Kissinger’s direction, Smith proposed that to resolve the BMD impasse, both superpowers could agree to each deploy a single BMD site around their capitals, preventing decapitation while abstaining from national defense. Kissinger expected the Soviets to reject this proposal, as Nixon had intended to use the Soviet rejection to push Congress towards accepting an expansion of Safeguard. However, after prolonged talks, Defense Secretary Melvin Laird and NSC Staffer Helmut Sonnenfeldt reported back that the Soviet stance was equivocal, even positive at the prospect of a limited BMD treaty. However, they regretted that this would only produce an undesirable reaction in Congress, granting the Democratic opposition a strong case to push for a unilateral BMD ban, rather than holding out for the wider strategic advantages Nixon and Kissinger still coveted.

Because of this, Smith was ordered to recant on the NCA proposal, the option he himself had suggested, prompting deadlock and stagnation in SALT. While the talks stagnated, that August, the CIA noted a substantial deceleration in the Soviets national BMD plans, discerning that the Kremlin had probably done so in “recognition that the system could be defeated by a determined attack using tactics of either saturation ... or exhaustion.” The Soviet position on BMD, judged the U.S. delegation’s lead CIA analyst, Raymond Garthoff, was tied to a wider Soviet bid to enlist Washington in a de facto alliance against China, against whom these limited systems were clearly directed. But because Nixon and Kissinger still hoped to play Beijing against Moscow, consensus over the Chinese threat was limited, and the deadlock became acute.

In December 1970, the Soviet delegation formally proposed concluding an BMD agreement as a first step in SALT, leaving offensive forces for a subsequent agreement. This was prompted by Kissinger’s back-channel diplomacy with the Soviet ambassador to the United States, Anatoly F. Dobrynin. Kissinger had expressed U.S. willingness to consider a limited BMD agreement, but failed to clarify specifics, undermining the U.S. negotiators in Vienna who then still pressed for a consensus on offensive forces. The whole drama of SALT in 1970 appears to have been one of hedging bets on the U.S. side, after Nixon discovered out he couldn’t spin the Soviet position on BMD to justify expanding Safeguard to Congress, and luckless attempts by the Kremlin to reframe SALT into an anti-China treaty.

1971 | BREAKTHROUGH

In 1971, while SALT negotiations alternated between Helsinki and Vienna, the U.S. and Soviet delegations maintained their separate positions on BMD. The Soviets insisted that a BMD Treaty must precede negotiations on offensive weapons, whereas the U.S. insisted upon addressing both issues simultaneously. The only important dynamic became Kissinger’s back-channel diplomacy with Dobrynin, which over time nearly bankrupted Smith’s authority in SALT. In May, Kissinger and Dobrynin finally agreed that a treaty on BMDs could precede one on offensive forces if the superpowers agreed to temporarily freeze their nuclear arsenals. The consensus Kissinger and Dobrynin reached would become the foundation of the ABM Treaty and its sister, the Interim Agreement on SALT (SALT I). But in truth, the sudden breakthrough prompted by Kissinger was tied to separate progress in his “ping pong” diplomacy with Beijing.

In April, Kissinger had finalized plans for his secret visit to China, coordinating with Zhou Enlai, Chairman Mao Zedong’s Foreign Minister. His breakthrough with Dobrynin was intended to accelerate momentum in SALT before putting a brand new fait accompli to the Kremlin. On July 9th, Kissinger arrived in Beijing and spent two days outlining the requirements to normalize Sino-American relations for the first time since World War II. Nixon revealed Kissinger’s visit to Beijing in a televised address on July 15th, and announced his intention to accept Mao’s invitation and visit Beijing himself in 1972. On July 19th, Kissinger met with Dobrynin to gauge his reaction to the development in preparation for another round of SALT. Kissinger noted that Dobrynin had become “totally insecure.” As the conversation continued, he criticized Dobrynin’s anti-China grievances as “grudging and petty,” before the ambassador’s tune reluctantly changed as he sobered to the new reality. This was all part of Nixon and Kissinger’s game to implement “triangular diplomacy” to plummet the Soviet Union to new depths of strategic inferiority as they simultaneously drew closer than ever to consensus on BMD and strategic arms.

From August to October, the SALT negotiations accelerated considerably. In Congress, Nixon had proposed expanding Safeguard’s role to providing area defense around Washington D.C., but failed to garner sufficient support. Nevertheless, the Soviet delegation offered a compromise that allowed each superpower to deploy two BMD sites, one to defend the capital and another to defend an ICBM field. However, they sought guarantees from the U.S. that they would avoid deploying Multiple Independently-Targetable Reentry Vehicle (MIRVed) missiles, which could oversaturate Galosh’s sensors and thereby reduced its overall credibility. Predictably, the U.S. flatly refused. However, by the end of 1971, the two-site proposal gained Nixon’s blessing, as it granted him the ability to reapproach Congress on the NCA option on a later date without relinquishing any real leverage. It appealed to the Soviets as by accepting the two-site agreement, the U.S. would be forced to close down the second Safeguard site in Montana. As 1971 ended, the SALT negotiators declared a breakthrough, and predicted that superpower treaties on both BMD and on offensive forces were just around the corner in 1972.

1972 | SUCCESS & FAILURE

In a shocking display of the failure of linkage, in March 1972, despite the improvements in relations with China and the Soviet Union, North Vietnam launched the Easter Offensive, a massive conventional invasion of South Vietnam. In April, after successfully repulsing the attack, Nixon initiated Operation Linebacker, bombing Hanoi and North Vietnam and mining Haiphong Harbor. In the rapid escalation, U.S. munitions accidently destroyed four Soviet merchant ships, threatening to revive superpower tensions at a critical juncture in SALT. Linebacker coincided directly with the seventh and final round of negotiations before the Moscow Summit, and despite the apparent necessity to ensure progress, the U.S. delegation only placed surplus pressure on the Soviets by continuing to threaten to enlarge Safeguard. Luckily, cooler heads prevailed and the final contours of the agreement were worked out without any last minute developments. On May 26th, the Moscow Summit began on schedule, and Nixon and Brezhnev signed the ABM and SALT I Treaties.

In its first iteration, the ABM Treaty allowed each superpower to deploy two BMD sites to defend their capital and an ICBM field. It clarified that no more than 100 interceptors could be stationed at each site, and placed strict limitations on the implementation of futuristic technology, another issue which had held up negotiations. It provided mechanisms for mutual verification, and enabled each superpower to continue to research, but not deploy, BMD technologies. The interim agreement on offensive forces, SALT I, froze the number of ICBMs and SLBMs both superpowers agreed to deploy over the next five years, and required another agreement in 1977 to finalize. The ABM and SALT treaties were widely supported by public opinion in the U.S., U.S.S.R. and Europe, granting Nixon and Kissinger a considerable political victory mere months before the 1972 U.S. Presidential Election, which Nixon won by a landslide.

Nixon and Kissinger had focused on the ABM Treaty and SALT, alongside normalization of U.S. relations with China, as prerequisites for peace in Vietnam. According to linkage, if the Kremlin and Beijing became invested in their relationships with the United States, the Viet Minh would become isolated from their Communist allies, and forced to sue for peace. To test this paradigm, Nixon secretly dispatched Kissinger to Paris to meet with Hanoi’s negotiator, Le Duc Tho, to extract a favorable peace agreement. In this case, linkage appeared to be vindicated after Tho made a breakthrough proposal inspiring Kissinger to conclude that “peace was at hand.”

After the negotiations continued throughout October and November, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu, who had been uninformed of Kissinger’s deliberations with Hanoi, became furious and refused to support the treaty. Thieu’s public rejection and mischaracterization of the treaty caused a diplomatic breakdown on December 16th, when the North Vietnamese delegation walked away from the talks. Nixon put an ultimatum to Hanoi to return to the negotiations within 72 hours. But Hanoi remained defiant, and Nixon was forced to launch Operation Linebacker II, colloquially dubbed “The Christmas Bombings” on December 18th. The superpower consensus established with Moscow and Beijing could not bring the Viet Minh back to the table. Ironically, this time linkage demonstrated a capacity to fail on the U.S. as well as Communist side.

1973-4 | ENDGAME

At this point, in light of overwhelming domestic pressure, Nixon had shifted tactics in Vietnam to endorse “Vietnamization,” the transfer of responsibility for South Vietnam’s security from the U.S. military to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). On January 27th, by signing the Paris Peace Accords, Nixon formally committed to this policy, leaving only a remnant of Marines in Saigon alongside a host of military advisors. However, throughout 1973-1975, the ARVN would gradually diminish as a fighting force as the Viet Cong gradually gained control of the South. Despite Nixon and Kissinger’s improvement of relations with Moscow and Beijing, neither the Soviet Union nor China proved willing or able to stop Hanoi from finishing the fight.

After signing the ABM Treaty, Nixon and Kissinger had committed to Safeguard and sanctioned the Kremlin’s Galosh, despite harboring enduring reservations over BMD. Moreover, Nixon was unable to obtain Congressional funding for the expansion of Safeguard around Washington D.C., leaving U.S. missile defenses in a relatively inferior position. In August, after the Kremlin tested its first MIRVed missile, the newly minted Secretary of Defense, James R. Schlesinger amended Safeguard’s program decision and placed additional funding into the program. Schlesinger was concerned that despite the progress made in SALT I and towards SALT II, the Soviet numerical advantage in ICBMs was continuing to increase. With the threat of MIRVed missiles, Schlesinger began to emphasize the need to assure Safeguard’s credibility, bringing him into conflict with Kissinger, who still saw Safeguard as a bargaining chip. Kissinger regained the upper hand over Schlesinger after becoming the single National Security Advisor and Secretary of State on September 23rd, assuming unprecedented control of both national strategy and U.S. diplomacy.

In October, SALT II negotiations remained at a standstill, but was reenergized by the unexpected outbreak of the Yom Kippur War between Egypt and Israel. Since the Six Day War in 1967, the superpowers had attempted to stabilize relations between their Middle Eastern allies as their own relations improved at the top through the détente produced by SALT. But Cairo and Tel Aviv remained hostile, and on October 6th, an Arab coalition of Egyptian and Syrian forces reinitiated hostilities by invading Israel on the Yom Kippur holiday. In response, on October 7th, Nixon authorized Operation Nickel Grass, an emergency airlift to resupply Israel. Shortly afterwards, Moscow began resupplying its allies, Egypt and Syria. On October 9th, in the ongoing SALT II negotiations, the Soviets offered a groundbreaking proposal, limiting MIRVed missiles to be a portion of each superpower’s total ICBM and SLBM arsenals. By October 20th, Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) were within 10 miles of Damascus, prompting Soviet delegates in the United Nations to call for an immediate ceasefire. Nixon agreed, and with the backing of the Security Council, the UN adopted Security Council Resolution 338, calling for an end to the hostilities.

On October 24th, the ceasefire came into effect in Syria, but the war with Egypt continued. The Kremlin threatened to intervene by sending troops into Egypt, prompting Nixon to place U.S. strategic forces on DEFCON III alert, in essence the highest stage of nuclear readiness. The next day, the Kremlin withdrew its threat to intervene, and on October 28th, Egyptian and Israeli leaders signed a ceasefire agreement. This time, the dramatic rise in superpower tensions was apparently unrelated to SALT, as the proposal which broke the deadlock came from the Soviet side and days before Nixon’s nuclear threat. The negotiations continued after the brief nuclear crisis and embraced the breakthrough. But Nixon’s demonstrated impulse to impose “Madman Theory” during the Yom Kippur War could have easily derailed SALT II, and served no apparent purpose in the negotiations other than to place them in needless jeopardy.

As Nixon’s presidency unraveled amidst the Watergate scandal, the SALT II negotiations became increasingly influenced by both domestic political pressures and Kissinger’s personal agenda. The domestic pressures eventually eroded Nixon’s political capital, and impaired his ability to implement foreign policy initiatives. By April, as Nixon became increasingly consumed by the domestic political crisis, he granted Kissinger full authority in the ongoing SALT II negotiations. Kissinger quickly used this singular authority to settle his row with Schlesinger over Safeguard by pushing for a new protocol to the ABM Treaty that forcibly contracted the system.

The final ABM protocol, shaped largely by Kissinger, represented a delicate balancing act that would define the limits of BMD for years to come, even as Nixon’s own presidency collapsed. By July, Kissinger finalized the new protocol, which reduced the number of BMD sites each superpower agreed to deploy by half, from 2 to 1. Each superpower could choose whether to use BMD to defend their national capital or an ICBM field, with a one-time right to switch. This allowed Nixon to gracefully bow out from his request to expand Safeguard to Washington D.C. while maintaining the North Dakota Safeguard system, and still allowing a future president to legally shift tactics. Kissinger designed the protocol to appeal to both factions in Congress and a variety of U.S. agencies, but enraged Schlesinger and other Cold Warriors by placing such harsh limitations on Safeguard while allowing the Soviets to consolidate their advanced BMD system around Moscow. On July 3rd, Nixon and Brezhnev signed the ABM protocol in Moscow. Just over a month later, Nixon would resign as a result of the Watergate allegations, having seen the Safeguard gambit through.

CONCLUSION

Nixon and Kissinger gained power in 1969 determined to bring about lasting strategic stability in the nuclear arms race, implement triangular diplomacy to the Kremlin’s disadvantage, and to end the Vietnam War. Safeguard comprised one of many tools in their intricate strategy to accomplish all of these ends simultaneously. Nixon and Kissinger effectively learned from the mistakes of previous administrations which had sought to develop BMD systems or had avoided doing so to procure strategic stability with the Kremlin. But they failed to learn the lessons from previous administrations’ attempts to extricate America from Vietnam, notably by failing to view Hanoi as an independent actor, significantly unaffected by wider geopolitical dynamics. As a result, they needlessly escalated this war in an effort to place maximum pressure on a Soviet leadership they had already maneuvered into a corner. Examining Nixon and Kissinger’s ends independently, their gambit to use Safeguard as a bargaining chip paid off exactly as they had hoped. However, upon examining the collateral damage, it emerges as questionable that this was in America’s best interests nor the long-term interest of procuring a stable balance of power.

This was evident in April 1975, when the last U.S. marines were airlifted from the U.S. embassy in Saigon, marking an inglorious end to a devastating war that cost over 58,000 Americans and nearly 3 million Vietnamese their lives. Had “peace with honor” been the true imperative, the Nixon Administration would have prioritized a direct resolution to the Vietnam conflict. Instead, the marriage of Nixon’s “Madman Theory” with Kissinger’s linkage concept perverted Johnson’s initial vision for SALT, resulting in a counterproductive strategy that escalated both the Vietnam War and the BMD debate in a bid to strong-arm the Kremlin and the Viet Minh alike. Nixon and Kissinger’s attempts to resolve all gaps in U.S. leverage without granting any edge to their adversaries whatsoever was far too ambitious a strategy to produce desirable results. Their endorsement of Safeguard as a method for national defense was one instance among many in which they misled the American public as to the nature of U.S. objectives and strategy, sowing superfluous homeland mistrust in addition to dread in Vietnam.

The Safeguard program’s trajectory remained riddled with contradictions. On September 28th, 1975, as it was officially declared operational, the House Appropriations Committee was already advocating for its deactivation. Reduced to a single site in North Dakota, the system nevertheless consumed $23 billion ($187 billion in 2025) before its termination. In November 1975, Congress voted to end the program, and President Ford signed the deactivation bill on February 9th, 1976. Moscow, meanwhile, continued to develop its Galosh system, to the anxieties of U.S. officials like Schlesinger. From its inception to its demise, Safeguard’s security rationale was fraudulent, failing to deliver tangible military benefits nor enduring agreement in the BMD debate, even if it did help limit the scope of Soviet BMD ambitions through the ABM Treaty.

Even in their improvement of relations with the superpowers, Nixon and Kissinger could have likely achieved better results without their Machiavellian methods. By conducting back-channel diplomacy with Dobrynin, Kissinger turned the SALT negotiations into a sham by undermining the U.S. and Soviet delegates sitting in Vienna and Helsinki attempting to broker an agreement. With regard to China, Kissinger’s overture was a stroke of political genius, but was handled in such a way as to intentionally provoke as visceral a reaction in Moscow as possible. Even if the result of this strategic exacerbation ensured short-term favorable outcomes in SALT, Kissinger’s grievous treatment undermined U.S-Soviet relations on a personal and psychological level. This reduced goodwill in SALT on matters including BMD, and could have easily provoked the Soviets to walk away from the negotiations altogether. Although the ABM and SALT Treaties were considerable steps towards ensuring strategic stability in the 1970s, in certain dimensions worthy of emulation, the fact that they failed to end the Cold War for good attests to Nixon and Kissinger’s failures to broker lasting trust.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Burr, William, ed. “The Secret History of the ABM Treaty.” National Security Archive. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB60/.

Burr, William, ed. “The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict, 1969: U.S. Reactions and Diplomatic Maneuvers.” National Security Archive. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB49/.

Dobrynin, Anatoly. In Confidence: Moscow’s Ambassador to America's Six Cold War Presidents (1962-1986). New York: Times Books, 1995.

Nixon, Richard M. RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978.

“Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty; Implementation of Safeguard System.” U.S. Department of State Archive. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/frus/nixon/e2/c22086.htm.

Smith, Gerard C. Doubletalk: The Story of SALT I by the Chief American Negotiator. New York: Doubleday, 1980.

Garthoff, Raymond L. Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1985.

Secondary Sources

Caldwell, Dan. “The Legitimation of the Nixon-Kissinger Grand Design and Grand Strategy.” Diplomatic History 33, no. 4 (September 2009): 633-652. Accessed February 14th, 2025.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44214073.

Crawford, Timothy, and Khang X. Vu. “Arms Control and Great-Power Politics.” War on the Rocks. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://warontherocks.com/2020/11/arms-control-and-great-power-politics/.

Garrity, Patrick J. “Nixon and Arms Control.” Presidential Recordings Digital Edition. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://prde.upress.virginia.edu/content/nixon_SALT.

Kimball, Daryl. “The Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty at a Glance.” Arms Control Association. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/anti-ballistic-missile-abm-treaty-glance.

Lang, Sharon Watkins. “SMDC History: Safeguard to BMD.” US ARMY. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://www.army.mil/article/145270/smdc_history_safeguard_to_bmd.

Litwak, Robert S. Détente and the Nixon Doctrine: American Foreign Policy and the Pursuit of Stability, 1969-1976. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Schwartz, Stephen I. “Missile Defense.” Brookings. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/missile-defense/.

Spinardi, Graham. “The Rise and Fall of Safeguard: Anti-Ballistic Missile Technology and the Nixon Administration.” History and Technology 26, no. 4 (2010): 313-334. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/14789898/SPINARDI_The_Rise_and_Fall_of_Safeguard.pdf.

Stephens, Elizabeth. “The Yom Kippur War.” History Today. Accessed February 14th, 2025. https://is.muni.cz/el/fss/podzim2015/MVZ244/The_Yom_Kippur_War.pdf.