The Wolfowitz Doctrine: A Blueprint for American Hyperpower?

How one 1992 defense report revealed the neoconservatives' strategy to extend American global dominance into the post-Cold War era. An article based on my dissertation research

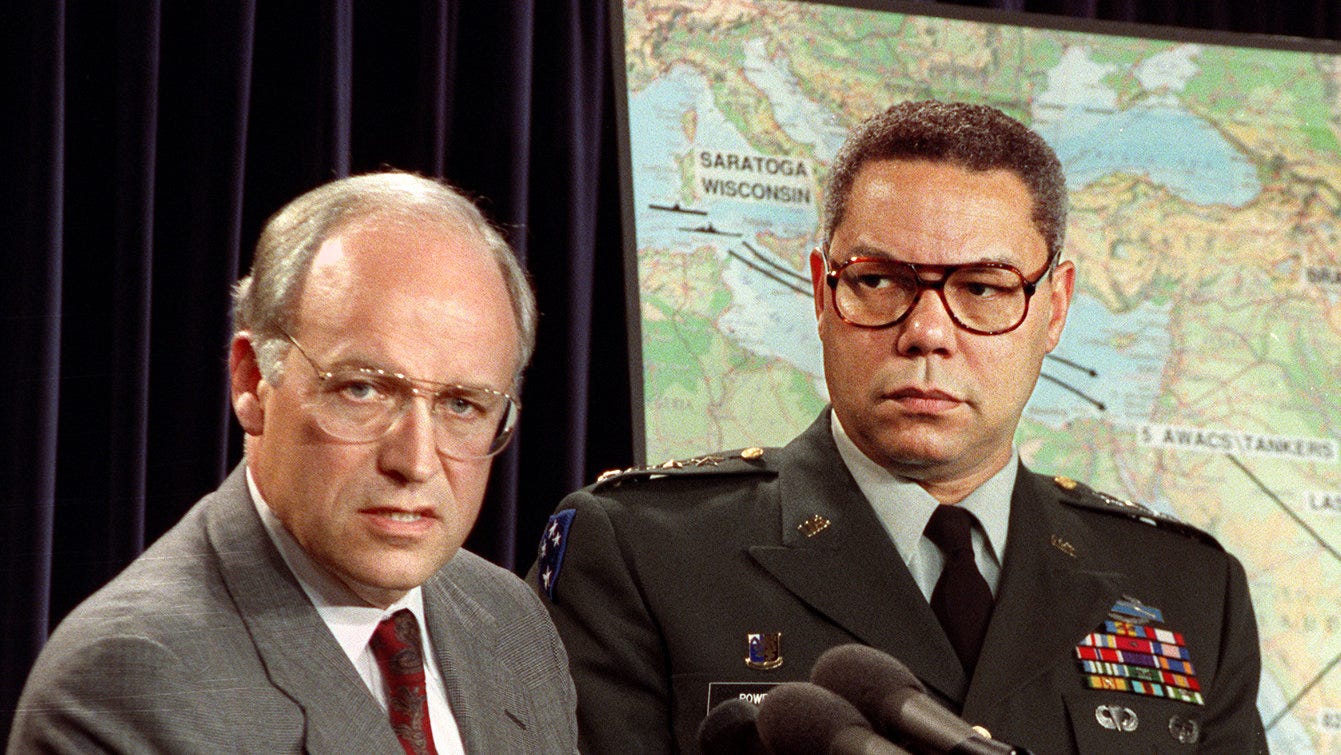

Dick Cheney and Colin Powell at a Pentagon briefing on the Persian Gulf, August, 1990

Introduction: A Defense Strategy for a One-Superpower World

In early 1991, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney ordered Paul Wolfowitz, his Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, to oversee the completion of a Defense Policy Guidance (DPG) outlining a military strategy capable of maintaining American global dominance into the post-Cold War era. Initially, the challenges which Cheney sought to premeditate were associated with the end of the Cold War and improved US-Soviet relations. But as 1991 became 1992, Cheney encouraged Wolfowitz to embrace lessons learned in the First Gulf War, and, eventually, to strategize for the formal collapse of the Soviet Union, and the emergence of a one-superpower world dominated by the U.S.

By the time the DPG was completed in December 1992, it was nothing less than a blueprint for maintaining U.S. hegemony into the post-Cold War era, formalizing the United States as a global hegemon with a “preeminent” responsibility to intervene in foreign affairs. It also included essential prescriptions for how to deal with nations considered the most likely to challenge, upset, or endanger this new global order: rogue states.

Before it was completed, the DPG was leaked to The New York Times by a concerned staffer who believed that the debate over the United States’ post-Cold War strategic posture should be carried out in the “public domain.” Patrick E. Tyler published an excerpted copy of the DPG on March 8th, 1992 under the provocative header “U.S. Strategy Plan Calls for Insuring No Rivals Develop.” It quickly sparked criticism from the American public, whose confidence in George H.W. Bush’s gross international commitments had become strained after successive American interventions in Panama, Iraq, and Somalia. Rising Democratic candidate Bill Clinton criticized the DPG as an effort by the Pentagon to “to find an excuse for big budgets instead of downsizing” after the end of the Cold War. Bush senior would distance himself from the project, but not repudiate the design. Pentagon officials would next downplay the criticism, arguing that the DPG was still in a pre-decisionary phase and didn’t reflect the Secretary’s final design.

But in an interview with Council on Foreign Relations scholar James Mann, Zalmay Khalilzad, one of the DPG’s main drafters and a future George W. Bush aide, Khalilzad would disclose that Cheney had actually been immensely satisified with the early, controversial design. In fact he had praised Wolfowitz, Khalilzad, and the DPG team: “You’ve discovered a new rationale for our role in the world.” Mann and others would confirm that even in the DPG’s final drafts, while certain phrases had been “toned down,” it had not been meaningfully altered.

In 2004, Mann would publish an article entitled “The True Rationale? It's a Decade Old” identifying the DPG as the first step in the neoconservatives’ long march towards the Iraq War. The DPG drafters, Mann argued, aimed to “to lay out the intellectual blueprint for a new world dominated -- then, now and in the future -- by U.S. military power.” In the process, they would steer U.S. defense policy towards confronting the “irrational, unpredictable” threat posed by rogue states in the Third World, a task which would ultimately prove the undoing of American global hegemony.

Preventing the Reemergence of a Superpower Rival

The aspect of the DPG which has attracted the most attention was the early drafters’ declared intention to “prevent the reemergence of a superpower rival,” thereby assuring the continuation of American global dominance. But the countries which the drafters identified as potential superpower adversaries appear strange by today’s standards: Germany and Japan. Much of this has to do with the democratic triumphalism of the early 1990s, spurred on by neoconservative intellectuals like Francis Fukuyama in his 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. Conservatives in the Straussian orbit took for granted that with the demise of the USSR, the top echelon of international relations could only be dominated by democratic capitalist countries. Japan and recently-reunified Germany were both young democratic nations with strong, growing economies, and the DPG drafters worried that either of these powers might one day attempt to carve out a sphere of influence for itself in East Asia or Europe.

To deter these nations from attempting to offset American military dominance, the DPG drafters recommended the United States military take concrete steps to retain its technological superiority, develop rapid reconstitution capabilities in multiple theaters, and continue to field a robust forward military posture. In essence, as long as the United States stayed far enough ahead in military technology and strength, it could insure that neither Germany nor Japan could afford to challenge the status quo. In an indirect way, however, the assumptions which guided this decision had a more consequential effect on how the United States intended to deal with the world’s remaining illiberal, non-capitalist regimes, including the future rogues roster.

The Regional Defense Strategy

While democratic-capitalist nations were treated as ascendant, even rivals, smaller totalitarian powers later institutionalized as rogues were characterized as embittered bit players clinging to the margins of history. Just as a sore loser might be prone to flipping a chessboard, the few nations still unwilling to get behind the American-dominated status quo were characterized as “irrational” and potentially “dangerous.” While it was clarified that they posed only a fraction of the threat the Soviet Union had, their propensity for irrational behavior became the cornerstone logic for increasing defense prescriptions to counter them. Referencing these countries’ current intense political and economic crises, for instance, the DPG drafters concluded that states like North Korea and Cuba were more likely than ever to “take actions that would otherwise seem irrational.”

Colin Powell would later critique this basic idea in a 1999 Oral History interview, suggesting, “if you assume that any opponent is irrational then you can justify anything.” The neocons, many of whose interests were directly tied to those of the American military industrial complex, often characterized rogue states as “irrational” to justify increasing the American defense budget in a period of relative peacetime. But the characterization would prove a dangerous departure from the tried and true deterrence strategy of the Cold War era, in which granting one’s adversary the auspices of rationality had proved vital to predicting their behavior. By encouraging the defense community to prioritize its ability to counter an “accidental, miscalculated or irrational” attack from a rogue state, the DPG drafters pushed the Pentagon decisively towards a military strategy which proved increasingly detached from reality.

Iraq Becomes the Archetypical Rogue State

Since the Gulf War, Cheney had attempted to communicate to Congress that Desert Storm had “presaged… the type of conflict we are most likely to confront again in this new era.” The DPG provided Cheney with a platform to vindicate this thesis, which relied upon the distinction that though the United States faced fewer, less powerful adversaries in 1992, they might still prove more dangerous due to a propensity for irrational attack. By focusing on the lessons learned from Desert Storm, Wolfowitz, a Persian Gulf specialist, aimed to globalize lessons from the Gulf Crisis so as to make them applicable within a wider strategy to confront multiple rogue regimes across the world.

Wolfowitz and the DPG drafters portrayed Hussein’s actions during the First Gulf War as irrational, focusing first on his invasion of Kuwait and next on his use of Scud missiles to reinvigorate an ongoing debate over ballistic missile defense. But the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, some scholars have suggested, was not itself an irrational gamble on Hussein’s part.

Alex Roberto Hybel argues in Rationality Over Power: The Bush Administration and the Gulf Crisis (1993) that the invasion was a failure of deterrence on America’s part: CIA analysts had identified the buildup of Iraqi forces on the Iraqi-Kuwaiti border, but Bush, determined to improve US-Iraqi relations, had dispatched US Ambassador to Iraq April Glaspie to mend disputes. In her conversation with Hussein, she had stated that “we have no opinion on Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.”

Hybel and others argue that this could have been interpreted as a “green light” in Baghdad of American acquiescence to an Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. But at very least, the US had failed to signal to Hussein, a U.S. partner in the Persian Gulf, that an attack against Kuwait would not go unpunished. Nonetheless, Wolfowitz and the DPG team painted the assault in the DPG as an irrational, unpredictable gamble launched by a trigger-happy dictator.

With regard to Hussein’s use of Scud missiles, the DPG drafters focused on Hussein’s decision to launch hundreds of these into Israel after the initiation of Operation Desert Storm in January 1991. Israel had not been part of the international coalition, but Hussein had attacked them to draw them into the conflict, fracturing the coalition along Arab-Israeli lines. The move was fundamentally rational from Hussein’s perspective. The U.S. restrained Israel, but Wolfowitz and his team had little justification to use the episode to outline other scenarios of a “community of nations embracing liberal democratic values” threatened by a group of “international outlaws armed with ballistic missiles.” This furthered the case to reinvigorate ballistic missile defense (BMD) research, officially outlawed by the Détente I-era ABM Treaty (1972), as a BMD system would only be necessary if deterrence failed -- i.e., if an “irrational” enemy attacked at an unexpected time.

But all of these descriptions, which heightened the need for American military engagement around the world, fed into a larger imperative in the DPG to defend America’s “preeminent responsibility” to intervene on behalf of the international community in global conflicts. In many cases, Wolfowitz and Cheney advocated that America ought to embrace its unilateral responsibilities in these regional conflicts, furthering a discourse which would ultimately lead to later neoconservative attitudes towards “preemption” and “coalitions of the willing” during the George W. Bush Administration. In essence, the DPG laid the groundwork for much of what was to come when the neoconservatives returned to power in 2001.

The DPG: A Cheney Doctrine?

Cheney’s long-term vision to maintain and enhance U.S. global military dominance was upset by Clinton’s victory in the 1992 Presidential Election; the Secretary decided to break with tradition and publicize his findings, perhaps in an effort to pressure Clinton’s Pentagon into continuing them. Interestingly, Cheney subtitled his “Defense Strategy for the 1990s: The Regional Defense Strategy,” seemingly prioritizing the elements of the DPG which would prove the most consequential: American policies towards rogues in the Third World.

It was hailed by neoconservatives (somewhat misleadingly) as the “Wolfowitz Doctrine”, with historian John Lewis Gaddis praising it for its fundamental continuities with post-World War II US policy. The features which distinguished it from the Cold War era were in fact more troubling; its emphasis on unilateralism, its ideological presumption of American hyperpower, and, above all its undue inflation of the “irrational” rogue state threat.

While Clinton did not embrace the DPG’s philosophy, he did not repudiate it, nor supply a meaningful alternative of his own making. Subsequent defense reviews under Clinton, like the Bottom-Up Review (BUR) of 1993, and the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) of 1997, would appear to reaffirm the basic elements of the DPG’s global strategy. Clinton and his National Security Advisor, Anthony Lake, would continue to raise alarms about the “rogue state threat” but would demonstrate a preference for dealing with such threats on a multilateral basis. Throughout Clinton’s tenure, however, clashes with rogue states would fail to correspond with prescriptions in the DPG; rogues would devise rational strategies to subvert the United States, and seldom engage in periodic, meaningless attacks against US allies as the DPG drafters seem to have expected.

Though neoconservatives rallied against Clinton’s policies by forming groups like the Project for the New American Century in the 1990s, much of what they criticized were rooted in their own strategic oversights. When they returned to power in 2001, the neocons would double-down on many strategies outlined in the DPG, leading them to commit many consequential mistakes.